| Title |

Mens Detachable Collars: Early 1920s |

| Category |

| Catalog, gallery |

| Date |

|

early 1920s |

| Why It's Interesting |

|

Imagine a catalog illustrating–and naming–over a hundred different styles/types of detachable collars. I have several of these, and when I showed one to my students, these displays surprised and entertained them as much as anything else I have shown. Who even remembers that collars once came separate from shirts? One finds references in Robert Benchley and P. G. Wodehouse to the new soft collars–they were deemed sissyish. But the variety of collars and the names given them boggles the mind. This page is from one of my least impressive collar catalogs: “The Collar of Value” issued by Posner’s in Boston. It shows 48 styles of collars, each costing 10 cents, and 8 styles of shirt cuffs priced at 18 cents the pair: including Harvard Square and Harvard Bound. The collar names all start with the letter P. Some of the odder names included: the Ping, Piqua, Praca, Paneas, and Padras. More traditional names included: Perry, Patrician, Pontiac, Paris, Premier, Pilgrim, Puritan, and Paramount. Did men want such a diversity of collars? What purpose did such variety serve? Was it equivalent to the proliferation of specialty pieces within silverware settings? It seems clear from writings of the age that men found these stiff collars uncomfortable. [See P. G. Wodehouse's Ukridge.] Why did they put up with them, and was this discomfort why they soon disappeared? |

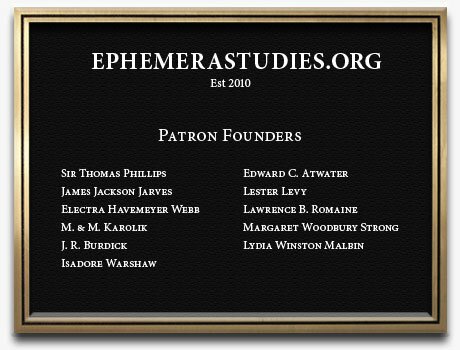

This website seeks to encourage researchers and collectors to discover and study obscure ephemera that document American culture and life. Worldcat reveals that most of the items that I post cannot be found in more than a few research libraries–often none at all. Alternately, research libraries do not bother to catalog ephemeral publications like these. I believe, however, that because these were distributed free, or at nominal cost, to consumers, they were the publications most likely to make their way into homes and be read by large numbers of Americans.

I acquire pre-1960 examples of the kinds of publications that prove so useful when scholars study 19th-Century America. The limited competition that I encounter for them suggests that libraries, which could easily outbid me, have little interest in post-Civil War and 20th-century ephemeral publications in general.

I try to anticipate what materials future historians will find useful. Being an historian first and a collector second, I organized this website to encourage others to do this too—even if this means new competition for me. I am aware that I could be wrong in prizing particular ephemera or even whole classes of ephemera. I may even be wrong to encourage scholars to study obscure ephemeral publications; these may be obscure for good reason.

Ephemerastudies.org will permit me to share with others the information and imagery that I am acquiring, and to benefit from the knowledge, intelligence and experience of other scholars and collectors. Please contact me with your impressions of the site.